Introduction: The Revolutionary Southern Belle

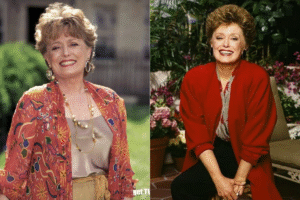

Blanche Elizabeth Devereaux stands as one of television’s most groundbreaking characters, a woman who shattered stereotypes about female sexuality, aging, and desirability with every sultry glance and perfectly timed double entendre. Portrayed by the incomparable Rue McClanahan in NBC’s “The Golden Girls” (1985-1992), Blanche transformed what could have been a caricature of Southern femininity into a complex, revolutionary character who challenged America’s puritanical attitudes about older women’s sexuality.

In an era when women over 50 were expected to be grandmother figures devoid of sexual desire, Blanche Devereaux emerged as a force of nature—unapologetically sexual, devastatingly confident, and absolutely certain of her desirability. She wasn’t just breaking rules; she was rewriting them, proving that sexuality doesn’t expire at menopause, that desire doesn’t diminish with age, and that a woman’s worth isn’t determined by society’s narrow definitions of appropriate behavior.

Early Life and Southern Roots

Atlanta Beginnings

Blanche Elizabeth Hollingsworth was born into privilege in Atlanta, Georgia, though the exact year remained deliberately vague—a Southern lady never tells her age. Born into a wealthy family with deep Southern roots, Blanche’s childhood was shaped by the traditions, expectations, and contradictions of the Old South. Her family’s estate, Twin Oaks, represented both the grandeur and the burden of Southern aristocracy.

Growing up in Atlanta’s high society meant Blanche was groomed from birth to be the perfect Southern belle: beautiful, charming, accomplished in social graces, and trained to catch and keep a suitable husband. These early lessons in femininity as performance would shape Blanche’s entire approach to life, creating a woman who understood that sexuality and charm were forms of power in a world that offered women few other options.

The Hollingsworth Family Dynamic

Blanche’s relationship with her family was complex and often painful. Her father, Curtis “Big Daddy” Hollingsworth, was a larger-than-life figure whose approval Blanche desperately sought but rarely received. His preference for her sister Virginia created deep insecurities that Blanche masked with bravado but never fully overcame.

Her mother, though less prominently featured in Blanche’s stories, contributed to the complicated family dynamic. The pressure to be the perfect Southern daughter while competing with siblings for parental attention created a woman who would spend her life seeking validation through romantic conquest while simultaneously maintaining that she needed no one’s approval.

The Burden of Beauty

From an early age, Blanche learned that her beauty was both her greatest asset and her defining characteristic. This early emphasis on physical appearance as currency would profoundly influence her self-perception and relationships. While this gave her confidence and social power, it also created deep anxieties about aging and a tendency to define her worth through male attention.

Her stories of teenage beauty pageants, cotillions, and the endless parade of suitors painted a picture of a young woman who learned early that desirability equals value—a lesson she would spend decades both embracing and struggling against.

Marriage to George Devereaux

The Great Love

George Devereaux represented the love of Blanche’s life, though their relationship was far more complex than her romanticized memories initially suggested. Their marriage, lasting several decades until George’s death, provided Blanche with stability, passion, and the framework within which she built her identity as wife and mother.

George, by Blanche’s accounts, was both devoted husband and enthusiastic lover. Their sexual chemistry remained strong throughout their marriage, establishing the foundation for Blanche’s belief that passion need not diminish with time. This successful long-term relationship gave Blanche the confidence that she could attract and satisfy men, a confidence that would define her widowhood.

Infidelity and Forgiveness

The revelation that Blanche had been unfaithful during her marriage added crucial complexity to her character. Her affair during a period of marital distance showed that even the “perfect” Southern marriage had its challenges. More importantly, her deep guilt about this infidelity, particularly given George’s subsequent death, revealed vulnerability beneath her confident exterior.

This admission transformed Blanche from a potentially one-dimensional “man-crazy” character into a woman carrying real guilt and using hypersexuality partially as both punishment and validation. Her inability to forgive herself for this betrayal added psychological depth to her constant need for male attention.

Widowhood and Its Aftermath

George’s death from a car accident (or heart attack—the story varied) forced Blanche to confront life without the man who had defined her adult existence. His passing not only left her emotionally devastated but also financially vulnerable, leading to her need to take in roommates to maintain her home.

The transformation from wealthy wife to working widow managing a household budget represented a dramatic life change. Yet Blanche adapted, showing resilience and practical skills that contradicted her helpless Southern belle persona.

Life at 6151 Richmond Street

The Homeowner

Unlike her roommates, Blanche owned the house at 6151 Richmond Street, giving her a unique position in the household hierarchy. This ownership represented both her last connection to her life with George and her independence as a single woman. The house became her kingdom, decorated in her romantic style and serving as the stage for her many romantic encounters.

Her decision to take in roommates showed practical intelligence often hidden behind her flirtatious facade. Blanche recognized she needed both financial support and companionship, making a choice that would transform her life in ways she never anticipated.

Creating a Chosen Family

The evolution of Blanche’s relationships with her roommates from mere tenants to chosen family showed her capacity for deep, non-romantic love. Despite her initial intentions of simply collecting rent, Blanche found herself part of a support system that provided what her biological family often couldn’t: unconditional acceptance, honest feedback, and genuine care.

Her role as homeowner but equal friend created interesting dynamics. She could have wielded her ownership as power but chose instead to create a democratic household where decisions were made together, showing generosity and understanding of what makes a home versus a house.

Sexuality and Romance

The Revolutionary Sexual Agency

Blanche’s open sexuality was revolutionary for 1980s television. Here was a woman over 50 who not only had sexual desires but celebrated them, pursued them, and refused to apologize for them. In a culture that desexualized older women, Blanche’s active sex life challenged ageist assumptions and puritanical attitudes.

Her sexuality wasn’t just about physical pleasure; it was about agency, power, and self-determination. Blanche chose her partners, set her terms, and maintained control over her romantic life in ways that many younger female characters on television couldn’t.

The Men in Blanche’s Life

Blanche’s numerous romantic relationships ranged from one-night stands to serious commitments, each revealing different aspects of her character. Her attraction to younger men challenged age-gap double standards. Her relationships with married men showed moral flexibility that complicated her Southern belle persona. Her pursuit of wealthy men revealed practical considerations beneath romantic idealism.

Notable relationships throughout the series included Mel Bushman, who offered marriage but not passion; Jake, the caterer who challenged her class prejudices; and Rex Huntington, whose death during intimacy forced Blanche to confront mortality and vulnerability.

The Psychology of Desire

Blanche’s hypersexuality served multiple psychological functions. It validated her continued desirability in a youth-obsessed culture. It provided connection and intimacy after George’s death. It offered control in relationships where she might otherwise feel vulnerable. It served as both celebration of life and defense against death.

Her need for male attention, while sometimes portrayed as shallow, actually revealed deep insecurities about aging, worth, and lovability. The comedy of Blanche’s sexuality often masked the pathos of a woman terrified of becoming invisible or irrelevant.

Professional Life

The Art Museum Career

Blanche’s work at the art museum suited her perfectly, combining culture, social interaction, and opportunities to meet eligible men. Her position, while never extensively detailed, provided financial independence and professional identity beyond her role as widow or sexual being.

Her approach to work reflected her approach to life: charming, social, and always aware of opportunities for romance. Yet she maintained professionalism and competence, showing that her flirtatious nature didn’t preclude work ethic.

Other Ventures

Throughout the series, Blanche explored various professional and creative ventures. Her attempt at writing romance novels revealed artistic ambitions and understanding of desire’s narrative power. Her brief stint running a hotel in “The Golden Palace” showed adaptability and business acumen.

These ventures demonstrated that Blanche’s interests extended beyond romance, even if romance usually found its way into whatever she pursued.

Family Relationships

Her Children

Blanche’s relationships with her children—Rebecca, Janet, Biff, Doug, and Matthew—revealed the complexity of motherhood within her Southern belle identity. Her children’s occasional disapproval of her lifestyle created tension between her roles as mother and sexual being, reflecting society’s discomfort with maternal sexuality.

Rebecca’s visits particularly highlighted these tensions, with daughter often embarrassed by mother’s behavior while Blanche struggled to balance maternal duty with personal authenticity. These interactions showed that even the confident Blanche could be vulnerable to her children’s judgment.

Sister Virginia

The rivalry with her sister Virginia revealed deep-seated insecurities from childhood that persisted into adulthood. Virginia’s ability to win their father’s approval and her judgment of Blanche’s lifestyle triggered defensive behaviors and competitive instincts that showed how family dynamics shape us throughout life.

Their relationship demonstrated that even confident, successful adults can revert to childhood patterns when confronted with family, and that sibling rivalry doesn’t necessarily diminish with age.

Big Daddy

Blanche’s relationship with her father, Big Daddy, was perhaps her most psychologically significant. His withholding of approval and affection created a wound that never fully healed, driving much of Blanche’s need for male validation. Episodes featuring Big Daddy showed Blanche at her most vulnerable, desperate for recognition from the first man whose approval she sought.

The complexity of loving a parent who consistently disappoints you, while still craving their validation, added psychological realism to Blanche’s character and explained much of her behavior.

The Southern Belle Persona

Performance and Identity

Blanche’s Southern belle persona was both authentic identity and conscious performance. She genuinely embraced Southern traditions, values, and social codes while simultaneously using them strategically to navigate social situations and attract men.

This duality—sincere Southern woman and calculating performer—made Blanche fascinating. She could deploy Southern charm strategically while genuinely believing in Southern hospitality. She could manipulate with feminine wiles while authentically embracing feminine power.

Cultural Representation

Blanche represented a specific type of Southern womanhood rarely portrayed with complexity on television. She embodied both the grace and the burden of Southern femininity, the beauty and the constraints of belle culture, the hospitality and the hidden steel of Southern women.

Her character challenged Northern stereotypes about Southern women while also interrogating Southern culture’s own myths about femininity, sexuality, and propriety.

Friendship Dynamics

With Dorothy

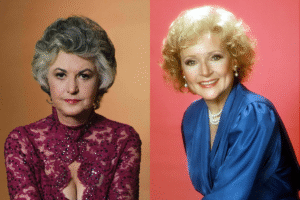

Blanche’s friendship with Dorothy created comedy through contrasts—Southern versus Northern, emotional versus intellectual, sexual versus reserved. Yet beneath these surface differences lay deep respect and affection. Dorothy’s sarcasm bounced off Blanche’s ego without causing real damage, while Blanche’s confidence sometimes inspired Dorothy to embrace her own desirability.

Their friendship showed that women with vastly different approaches to life and sexuality could support each other without requiring conformity.

With Rose

Blanche’s relationship with Rose was particularly touching. Despite Rose’s naivety sometimes frustrating her, Blanche showed protective instincts toward her innocent friend. She educated Rose about sexuality and relationships while respecting her different values, showing that Blanche’s hypersexuality didn’t require others to share her approach.

With Sophia

The dynamic between Blanche and Sophia provided some of the series’ best comedy. Sophia’s sharp tongue found perfect target in Blanche’s ego, yet their sparring masked genuine affection. Sophia’s age gave her license to puncture Blanche’s pretensions while also recognizing the vulnerability beneath the bravado.

Vulnerability and Depth

Aging Anxiety

Despite her confidence, Blanche harbored deep anxiety about aging. Her lies about her age, her consideration of plastic surgery, and her panic at signs of physical decline revealed terror at losing the beauty that had defined her worth since childhood.

These anxieties made Blanche relatable even to viewers who didn’t share her hypersexuality. The fear of becoming invisible with age, of losing one’s defining characteristics, resonated across different life experiences.

The Mask of Confidence

Blanche’s overwhelming confidence often served as armor against vulnerability. Her bravado protected her from rejection’s full impact, her sexuality distracted from deeper emotional needs, and her Southern charm deflected serious scrutiny.

Moments when this mask slipped—during family crises, health scares, or genuine heartbreak—revealed a woman far more complex than her confident exterior suggested.

Mental Health Struggles

Episodes dealing with Blanche’s psychological challenges, including her fear of intimacy after Rex’s death and her panic at aging, treated mental health with surprising sensitivity. Her therapy experiences and emotional breakthroughs showed that even the most confident people need help processing trauma and change.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

Sexual Revolution for Older Women

Blanche Devereaux helped launch a sexual revolution for older women on television. She proved that female sexuality doesn’t disappear with menopause, that desire doesn’t diminish with age, and that older women deserve representation as sexual beings.

Her character paved the way for more honest portrayals of older women’s sexuality in subsequent television shows and films, challenging ageist assumptions that persist in media and society.

Southern Femininity Reimagined

Blanche offered a new vision of Southern femininity that embraced tradition while rejecting constraints. She showed that a woman could be a lady and a sexual being, could honor Southern hospitality while pursuing her own desires, could embody grace while refusing to be diminished.

This reimagining influenced how Southern women were portrayed in media, moving beyond simple stereotypes to more complex representations.

LGBTQ+ Icon

Blanche became an unexpected LGBTQ+ icon, particularly in drag culture. Her performative femininity, dramatic sexuality, and unshakeable confidence resonated with communities that understood gender and sexuality as performance and choice rather than fixed categories.

Her acceptance of her gay brother Clayton, though initially challenging for her, showed growth and love triumphing over prejudice, making her an ally figure as well as icon.

Memorable Episodes and Storylines

“That Was No Lady”

When Dorothy’s ex-husband Stan falls for Blanche, the episode explored female friendship versus romantic interest. Blanche’s genuine struggle between loyalty to Dorothy and attraction to Stan showed that even she had lines she wouldn’t cross for romance.

“Journey to the Center of Attention”

Blanche’s jealousy when Dorothy gets more attention at a bar revealed deep insecurities about her desirability. The episode showed that even the confident Blanche could feel threatened and that her need for attention went beyond simple vanity.

“Beauty and the Beast”

When Blanche is pursued by a man in a wheelchair, her struggle with attraction versus societal expectations challenged both her and viewers’ assumptions about disability and sexuality. Her ultimate acceptance showed growth and the ability to see beyond physical perfection.

“Yes, We Have No Havanas”

Blanche’s relationship with Fidel Santiago, thinking he’s rich when he’s actually a cigar maker, revealed her materialism but also her capacity to value genuine connection over wealth when truly tested.

Fashion and Appearance

The Signature Style

Blanche’s fashion choices—flowing negligees, bold colors, and always-perfect hair and makeup—created a visual signature as memorable as her personality. Her style celebrated feminine sexuality, rejecting the notion that older women should dress conservatively.

Her attention to appearance wasn’t vanity but philosophy: presenting one’s best self to the world as a form of respect for oneself and others. This approach to personal presentation influenced how viewers thought about aging and style.

The Power of Presentation

Blanche understood that appearance was communication, that how one presents oneself shapes how one is perceived and treated. Her careful attention to her look wasn’t shallow but strategic, using fashion and beauty as tools for maintaining agency and visibility in a culture that often ignores older women.

Rue McClanahan’s Performance

Perfect Casting

Rue McClanahan brought depth, humor, and humanity to what could have been a one-note character. Her ability to deliver sexual content with class, to find vulnerability in confidence, and to make Blanche sympathetic even at her most narcissistic showed remarkable skill.

McClanahan’s own Southern background informed her portrayal, bringing authenticity to Blanche’s accent, mannerisms, and cultural references. She understood Southern womanhood’s complexities and brought that understanding to her performance.

Comic Timing and Dramatic Depth

McClanahan’s comic timing was impeccable, but her dramatic moments were equally powerful. She could shift from comedy to pathos within a scene, making Blanche’s emotional moments feel genuine despite the character’s often theatrical nature.

Her chemistry with the other cast members, particularly her ability to play off Betty White’s innocence and Bea Arthur’s sarcasm, created magic that transcended individual performances.

Conclusion: The Revolutionary Belle

Blanche Elizabeth Devereaux stands as one of television’s most revolutionary characters, a woman who refused to accept society’s limitations on female sexuality, aging, and desirability. Through Rue McClanahan’s brilliant performance, Blanche became more than entertainment—she became a statement about women’s right to remain fully human, fully sexual, and fully visible throughout their lives.

Her character challenged virtually every stereotype about older women: that they’re asexual, that they should be modest and reserved, that their value diminishes with age, that their stories aren’t worth telling. Blanche proved that a woman over 50 could be the most desirable person in any room, that confidence is ageless, and that sexuality is a lifelong gift rather than a youth-limited resource.

But Blanche was more than just a sexual revolutionary. She was a complex woman dealing with grief, family dysfunction, aging anxiety, and the challenge of rebuilding life after loss. Her vulnerabilities made her human, her insecurities made her relatable, and her growth showed that change is possible at any age.

The friendship between Blanche and her roommates demonstrated that chosen family can provide what biological family cannot, that women’s friendships deserve narrative centrality, and that differences in values and approaches to life can strengthen rather than divide friendships.

Blanche’s Southern identity added layers to her character, showing that regional culture shapes but doesn’t determine identity, that tradition and progress can coexist, and that femininity can be both performance and authentic expression.

For the LGBTQ+ community, Blanche became an icon of performative femininity, showing that gender expression is art, that sexuality is fluid, and that confidence comes from embracing rather than hiding one’s true nature.

Her impact on fashion and beauty standards for older women cannot be overstated. Blanche proved that style has no expiration date, that older women can be glamorous, and that attention to appearance is self-care rather than vanity.

The psychological complexity of Blanche’s character elevated “The Golden Girls” beyond simple sitcom. Her struggles with attachment, her narcissistic defenses against vulnerability, and her journey toward self-acceptance provided depth that rewarded careful viewing.

As society continues to grapple with ageism, sexism, and changing definitions of family and sexuality, Blanche Devereaux remains relevant. She reminds us that desire doesn’t diminish with age, that confidence is revolutionary, and that every woman deserves to be the heroine of her own story regardless of age.

From Atlanta belle to Miami libertine, from wealthy wife to working widow, from defensive narcissist to vulnerable friend, Blanche’s journey showed that life’s second acts can be more interesting than the first. She taught us that sexuality is power, that confidence is choice, and that a woman’s worth is determined by her own standards rather than society’s limitations.

Blanche Elizabeth Devereaux remains television royalty, a Southern belle who conquered hearts not through traditional feminine submission but through revolutionary feminine power. Her legacy lives on in every older woman who refuses to become invisible, in every person who chooses confidence over convention, and in everyone who believes that the best chapters of life might just be the ones that come after society says the story should end.